Round midday on July 26, 1950, a number of hundred South Korean villagers sat on a railroad embankment close to the hamlet of No Gun Ri. American troopers had ordered them there, searched their belongings, and promised secure passage south. Then the troopers left.

Planes abruptly strafed the gang of males, ladies, and kids. The survivors scrambled for canopy beneath a concrete railroad bridge as troopers opened hearth from close by positions. What adopted turned one of many deadliest acts dedicated by U.S. troops in opposition to civilians within the twentieth century.

For the subsequent three days, troopers of the seventh Cavalry Regiment poured rifle and machine gun hearth into the dual tunnels. Complete households huddled behind partitions of corpses. Moms shielded their kids with their our bodies. The survivors drank blood-mixed water from a stream operating via the underpass.

“Kids had been screaming in worry and adults had been praying for his or her lives, and the entire time they by no means stopped taking pictures,” mentioned Park Solar-yong, who misplaced her 4-year-old son and 2-year-old daughter within the carnage.

Catastrophe on the Korean Peninsula

The bloodbath occurred solely a month into the Korean Struggle. North Korean forces had invaded the South on June 25, 1950, catching American troops utterly unprepared. Activity Drive Smith, the primary U.S. unit to interact the enemy, was overrun on July 5. The twenty fourth Infantry Division misplaced its commander, Main Normal William Dean, as a prisoner of battle at Taejon on July 20.

The seventh Cavalry Regiment landed at Pohang-dong on July 18 as a part of the first Cavalry Division. This was Custer’s outdated regiment, the Garryowens, notorious for the catastrophe at Little Bighorn 74 years earlier. The troops had been having fun with occupation obligation in Japan. Half the regiment’s sergeants had not too long ago transferred to different items. Many troopers had been youngsters with no fight expertise.

The retreating Individuals they encountered made a terrifying impression on the brand new arrivals as they moved to the entrance.

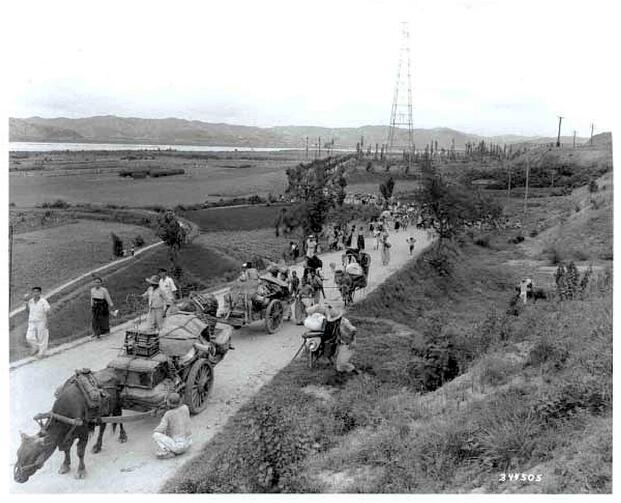

Fears of North Korean infiltration unfold quickly. Intelligence studies indicated enemy troopers had been disguising themselves as refugees to slide behind American traces. An estimated 380,000 South Korean civilians had been fleeing south in these chaotic first weeks, streaming via non-established entrance traces.

American commanders responded with drastic measures. On July 24, a communication logged on the eighth Cavalry Regiment headquarters said that refugees had been to not cross the entrance line. These attempting to cross had been to be fired upon. The order added a caveat to “use discretion in case of girls and kids.”

Main Normal William Kean of the twenty fifth Infantry Division likewise ordered that “all civilians seen on this space are to be thought of as enemy and motion taken accordingly.”

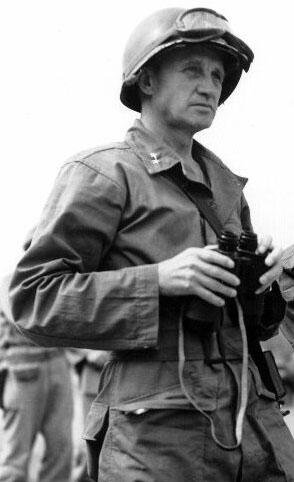

Main Normal Hobart Homosexual, commanding the first Cavalry Division, advised reporters he believed most civilians shifting towards American traces had been North Korean guerrillas. He would later describe refugees as “truthful recreation.” On August 4, after the No Gun Ri killings, Homosexual ordered the Waegwan bridge over the Naktong River blown whereas a whole lot of fleeing Koreans had been nonetheless crossing.

The Street to No Gun Ri

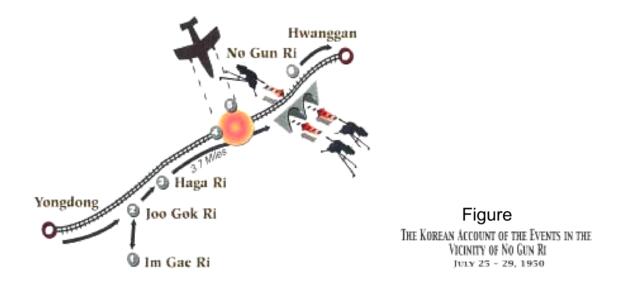

The villagers who died on the railroad bridge got here primarily from Chu Gok Ri and surrounding hamlets in Yongdong County, roughly 100 miles southeast of Seoul. On July 23, American troopers and a Korean policeman arrived and ordered them to evacuate. The realm would quickly develop into a battlefield.

Most residents fled to Im Ke Ri, a mountain village about two kilometers away. They believed they’d be secure there.

On the night of July 25, American troopers appeared at Im Ke Ri. They ordered the villagers to collect their belongings and promised to escort them to security close to Pusan. Between 500 and 600 folks set out on foot, main ox carts loaded with possessions, some with kids strapped to their backs.

The column spent one night time at Ha Ga Ri. The following morning, they continued towards No Gun Ri.

When the refugees reached the railroad crossing round noon on July 26, American troopers stopped them. The troops ordered everybody onto the tracks and searched their belongings. They discovered no weapons or proof that any of them had been guerillas.

Then, with out warning, the troopers departed. A number of plane appeared moments later and strafed the civilians.

Three Days of Killing

The air assault killed dozens instantly. Some survivors estimated that roughly 100 folks died on the railroad embankment earlier than anybody might attain shelter.

“Chaos broke out among the many refugees. We ran round wildly attempting to get away,” recalled Yang Hae-chan, who was 10 years outdated on the time.

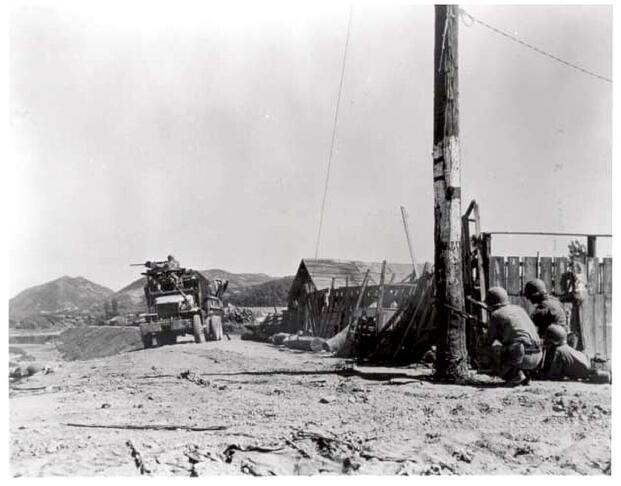

The survivors fled right into a small culvert beneath the tracks.

All of the sudden, American floor hearth drove them from there into a bigger double tunnel underneath a concrete railroad bridge. Every underpass measured roughly 80 ft lengthy, 22 ft broad, and 40 ft excessive.

The 2nd Battalion, seventh Cavalry Regiment had dug into positions on a ridge overlooking No Gun Ri. The unit was in poor form. On the night time of July 25, the troops had panicked and scattered throughout a disorganized retreat from their ahead positions close to Yongdong. Greater than 100 males went lacking earlier than the battalion was reorganized the subsequent morning.

Communications specialists Larry Levine and James Crume later mentioned they remembered listening to orders to fireplace on the refugees coming from the next degree, in all probability from 1st Cavalry Division headquarters.

A mortar spherical landed among the many refugees. Then got here what Levine referred to as a “frenzy” of small-arms hearth.

Machine gunner Norman Tinkler of H Firm mentioned he fired roughly 1,000 rounds into the tunnels. He noticed “plenty of ladies and kids” among the many white-clad figures on the railroad tracks.

“We simply annihilated them,” Tinkler mentioned.

Joseph Jackman of G Firm advised the BBC that his commander ran down the road shouting orders to fireplace. “Children, there was children on the market, it did not matter what it was, 8 to 80, blind, crippled or loopy, they shot ’em all,” Jackman mentioned.

“It was assumed there have been enemy in these folks,” mentioned ex-rifleman Herman Patterson, explaining the mindset. He additional added it was a bloodbath.

Thomas Hacha of the close by 1st Battalion watched the killing unfold. “I might see the tracers spinning round contained in the tunnel,” he recalled. “They had been dying down there. I might hear the folks screaming.”

Not everybody participated. First Lieutenant Robert Carroll, a 25-year-old reconnaissance officer with H Firm, mentioned he stopped a few of the sporadic taking pictures. When a younger baby operating down the tracks was hit, Carroll carried the wounded baby again to the tunnel the place the battalion surgeon was treating refugees injured by the firing.

Contained in the tunnels, these trapped piled corpses as barricades in opposition to the gunfire. Some tried to dig into the bottom with their palms. Racked by thirst, they drank from a small stream operating via the underpass, its water blended with blood.

“The American troopers performed with our lives like boys taking part in with flies,” mentioned Chun Choon-ja, who was 12 years outdated on the time.

By the second day, the fixed firing had lowered to potshots and occasional barrages every time somebody moved or tried to flee. Park Solar-yong watched her two kids die. She was badly wounded however survived by hiding among the many our bodies.

The seventh Cavalry withdrew within the predawn hours of July 29 because the American retreat continued. That afternoon, North Korean troopers arrived on the tunnels. They allegedly helped the survivors, roughly two dozen, principally kids, feeding them and sending them again towards their villages.

Buried Historical past

The bloodbath remained hidden from historical past for practically 5 many years.

Two North Korean journalists who arrived with the advancing troops reported discovering roughly 400 our bodies within the No Gun Ri space, together with 200 in a single tunnel. The survivors additionally estimated the demise toll at round 400.

Below the authoritarian authorities of South Korean President Syngman Rhee, the survivors feared retaliation in the event that they spoke publicly. One survivor, Yang Hae-chan, mentioned Korean police warned him to remain quiet about what occurred.

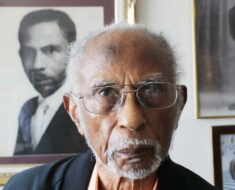

Former policeman Chung Eun-yong devoted his life to uncovering the reality. His spouse was Park Solar-yong, the girl who watched their two younger kids die within the tunnels. Chung filed his first petition to the U.S. and South Korean governments in 1960. Over the next many years, he and a survivors’ committee submitted greater than 30 petitions. Virtually all had been ignored.

Chung quietly gathered proof at archives in Seoul and Daejeon for 3 many years. In 1994, after South Korea’s transition to democracy, he revealed a novel based mostly on the occasions. Ten publishers had rejected it. The U.S. Army mentioned any killings of civilians occurred within the warmth of fight.

The breakthrough got here in 1999. Related Press reporters Sang-Hun Choe, Charles J. Hanley, and Martha Mendoza contacted Chung and started interviewing survivors and American veterans. They discovered declassified paperwork displaying orders to shoot civilians on the battle entrance.

On September 29, 1999, the AP revealed its investigation. A dozen seventh Cavalry veterans corroborated the survivors’ accounts. The story received the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting.

Although the investigation was not with out criticism. One witness quoted within the authentic story, Edward Day by day, was later discovered to have been not been current in the course of the bloodbath in any respect. He admitted to passing on secondhand info.

Apparently, Carroll was livid and later admitted his position within the story was twisted. He claimed no orders had been ever given to fireplace on the civilians and that no machine weapons opened hearth. He additional asserted he stopped a lone soldier from firing at refugees from a whole lot of yards away, who had did not hit anybody. When he went to the surgeon, he claimed solely a dozen refugees had been wounded, principally by shrapnel.

Patterson additionally famous that his description within the story of it being a bloodbath was him discussing what occurred to their unit in fight. He claimed he was not referring to the refugees in any respect. Many others quoted within the story said their roles or phrases had been twisted to suit the narrative.

Army historian, Main Robert L. Bateman, wrote “No Gun Ri: A Army Historical past of the Korean Struggle Incident” to counter lots of the claims within the AP story. He notes that it was the results of poor coaching, management and readiness at a time when the navy was advised to crack down on refugees shifting via their traces. In his view, there was no order to fireplace on civilians.

The Response

Each america and South Korea launched investigations following the AP report. The parallel inquiries lasted 15 months.

In January 2001, each governments launched their findings concurrently. The U.S. Army acknowledged for the primary time that American troopers had killed “an unknown quantity” of South Korean refugees at No Gun Ri with “small-arms hearth, artillery and mortar hearth, and strafing.”

Nevertheless, the Army concluded the killings had been “an unlucky tragedy inherent to battle and never a deliberate killing.” Investigators mentioned they discovered no proof that orders got to shoot the civilians.

South Korean investigators reached totally different conclusions. Their report mentioned 17 veterans of the seventh Cavalry testified they believed there have been orders to shoot the refugees. Two had been battalion communications specialists in an particularly good place to know which orders had been relayed.

The doc that might have settled the query was gone. The seventh Cavalry Regiment’s communications journal for July 1950, the file that might have contained any orders at No Gun Ri, was lacking from its place on the Nationwide Archives. Nobody might clarify why.

The survivors claimed the U.S. report downplayed the position of American commanders and troopers within the bloodbath. So did a few of the Individuals who helped produce it.

Former Congressman Pete McCloskey of California, a Marine veteran of the Korean Struggle and one in all eight exterior advisers to the Pentagon inquiry, reviewed the proof and agreed with the Koreans.

“I do not assume there may be any query that they had been strafing and underneath orders,” McCloskey mentioned. “I believed the Army report was a whitewash.”

Retired Marine Normal Bernard Trainor, one other adviser, wrote to Protection Secretary William Cohen that he believed American command was liable for the lack of harmless civilian life.

“On the very least, it failed to manage the hearth of its subordinate items and personnel,” Trainor wrote. “At worst, it ordered the firing.”

“This isn’t sufficient for the bloodbath of over 60 hours, of 400 harmless individuals who had been hunted like animals,” Chung Eun-yong mentioned.

President Invoice Clinton, within the closing days of his administration, issued an announcement of remorse. “Issues occurred which had been incorrect,” he mentioned. However the U.S. authorities rejected survivors’ calls for for an apology and compensation. Washington supplied as a substitute to construct a memorial and set up a scholarship fund. The survivors rejected the proposal.

Subsequent analysis revealed the Army had buried proof.

Investigators had not disclosed not less than 14 declassified paperwork displaying high-ranking commanders ordering or authorizing the taking pictures of refugees. These included leaders calling refugees “truthful recreation” and directing troops to “shoot all refugees coming throughout river.” The AP discovered these paperwork within the investigators’ personal archived recordsdata after the 2001 inquiry. None had appeared within the Army’s 300-page public report.

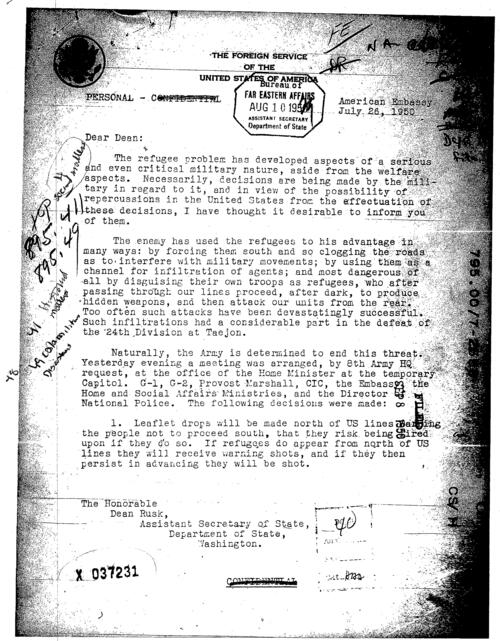

In 2005, historian Sahr Conway-Lanz found a letter from U.S. Ambassador John Muccio to the State Division dated July 26, 1950, the day the No Gun Ri killings started. It confirmed a coverage had been adopted to shoot refugees approaching U.S. traces after warning pictures had been fired.

The Army had examined this letter throughout its investigation. When South Korea requested about it, the Pentagon acknowledged it had seen the doc in 2000 however dismissed it. The Army claimed it outlined a “proposed coverage,” not an permitted one. However the letter itself said unambiguously that “selections made” at a high-level assembly included the coverage to shoot approaching refugees.

Legacy

South Korea’s Nationwide Meeting handed laws in 2004 establishing a committee to determine the victims. The next 12 months, officers licensed the names of 163 lifeless or lacking and 55 wounded, noting that many extra victims had been by no means reported.

The No Gun Ri Peace Basis estimates between 250 and 300 folks had been killed, principally ladies and kids.

A 33-acre peace park opened on the web site in 2011, constructed with $17 million in South Korean authorities funds. It features a memorial, museum, and training heart. The dual tunnels nonetheless bear bullet scars.

Chung Eun-yong died in August 2014 at age 91. His son, Chung Koo-do, now chairs the No Gun Ri Worldwide Peace Basis.

The bloodbath stands among the many deadliest incidents involving American forces and civilians within the nation’s trendy navy historical past. The Korean Struggle itself stays the deadliest battle for civilians as a proportion of whole casualties in any American battle.

No American soldier was ever punished for what occurred at No Gun Ri.

“America has no justice or conscience,” Chung Eun-yong later mentioned.

The reality took half a century to emerge. For individuals who made it out of these tunnels, the official acknowledgment got here many years too late. Even after the investigations, many veterans and organizations continued denying the bloodbath ever occurred. Others acknowledged it did, although downplayed their position or dismissed the notion that it was formally ordered. Some veterans and survivors proceed to claim that it occurred, was ordered by American commanders and was lined up.

However, the AP story and investigations led to many survivors of different American and authorities atrocities to come back ahead with their tales. This led to the institution of the Reality and Reconciliation Fee which uncovered different buried battle crimes and killings dedicated by U.S. forces in the course of the Korean Struggle.

Even as we speak, the bullet holes can nonetheless be seen within the concrete partitions of the tunnel at No Gun Ri. Whereas the precise variety of victims is unknown, it stays one of many deadliest and most horrific battle crimes dedicated by American forces in historical past.